General framework

Elements of context

Introduction to urban economic theory

“The standard urban model has shown us that the price of land in large cities is similar to the gravity field of large planets that decreases with distance at a predictable rate. Ignoring land prices when designing cities is like ignoring gravity when designing an airplane.”

- Alain Bertaud, Order without design (2018)

Urban shape may be seen as the result of two sets of forces:

State decisions, such as land-use regulations (e.g. zoning) and transport policies, and geographical constraints

Multiple decisions made by firms and inhabitants, through the real-estate and construction markets notably

The standard urban economic model - as envisioned by Alonso [1964], Muth [1969], Mills [1967], and formalized by Wheaton [1974] - aims at analyzing market forces operating under the constraints imposed by state decisions. It showcases three main mechanisms:

Households trading off between lower transportation costs and shorter commuting time when living close to the city center (where they work), vs. larger dwellings and lower rents in remote areas

Local amenities (e.g. a nice view) modulating rents locally

Investors optimizing housing density as a function of rents and construction costs

According to this model, if there is one major city center, rents and population density will be maximum there, and decrease when moving away. To reach this main conclusion (among others), the model makes a number of simplifying assumptions, most of which can be relaxed in more elaborate models to obtain more realistic results (see Duranton and Puga [2015]) 1.

The key hypothesis of this set of models is that, in the long run, land-use patterns reach a stationary equilibrium in which (similar) agents share a common utility level. Put in other words, they cannot reach a higher utility level by changing locations, which allows to rationalize the observed land-use patterns through optimization behaviours.

The interest of such models grounded in economic theory compared to other land use and transport integrated (LUTI) simulation models 2 lies in their relative tractability and potential for causal interpretation (Arnott [2012]).

Past and current developments

NEDUM-2D directly applies a discrete two-dimensional version of the standard urban monocentric model for residential land use with several transport modes (see Fujita [1989]) on a grid of pixels, accounting for zoning and land availability constraints defined at the pixel level. This allows for more realistic land-use patterns than the basic model with a linear city.

Furthermore, as indicated by its name, NEDUM-2D is a dynamic model that accounts for the fact that urban stationary equilibria may not exist: when population, transport prices, or incomes vary, housing infrastructure cannot adapt rapidly to changing conditions and is always out of equilibrium. To compute the dynamics, a static equilibrium at the initial state is computed first. Then, time-moving variables are updated and housing supply inertia is imposed as a constraint on the model. The dynamic equilibrium (for each subsequent period) is therefore obtained as a result of this new constrained optimization. If one is only interested in the long-term outcome and not in how the adjustments play out through time, one may just look at the static outcome of the model (with end values for time-moving variables).

Below is a non-exhaustive list of publications where NEDUM-2D has been used so far, classified by policy question:

A first set of papers look at urban climate policies.

Within the context of Paris, France, Viguie and Hallegatte [2012] study trade-offs and synergies between a greenbelt policy, a zoning policy to reduce flood risk, and a transportation subsidy. In particular, they find that flood zoning and greenbelt policies can only be accepted if combined with transportation policies. Avner et al. [2014] study the impacts of a carbon or gasoline tax more specifically and find that reducing commuting-related emissions requires lower (and more acceptable) tax levels in the presence of dense public transportation. Viguie et al. [2014] find that the main drivers of urban sprawl and climate and flood vulnerability appear to be local demographic growth and local policies, and not global factors such as energy and transport prices. A direct consequence is that very strict urban policies – including reconstruction – would become necessary to control emissions from urban transportation if technologies (global factors driving most of transport-related greenhouse gas emissions) reveal unable to do so. Biao et al. [2018] study the rebound effects associated with ride-sharing and find that they end up dividing the GHG emission savings by a factor ranging from 2 to 3. Coulombel et al. [2019] further disentangle between a route choice effect, a modal shift effect, a distance effect, and a relocation effect: they find that the observed rebound mostly comes from the modal shift effect, supplemented as ride-sharing develops by the distance effect. This has direct consequences as to the efficiency of complementary policies such as improving public transit, reducing road capacity or increasing the cost of car travel.

Within the context of Buenos Aires, Argentina, Avner et al. [2017] look at trade-offs and synergies between a public transport subsidy, an income compensation scheme and a construction subsidiy scheme. They find that the replacement of the transit subsidy by a lump-sum transfer is globally welfare-improving but leads to higher GHG emissions, and may have harsh redistributive impacts for captive transit users in some areas. Medium-term adjustments of land and housing prices would partially mitigate the negative impacts of higher transport costs for tenants, but would further hurt homeowners.

At the global scale, Liotta et al. [2022] look at trade-offs and synergies between four representative climate policies: bus rapid transit, fuel tax, fuel efficiency, and urban growth boundary (UGB). They find that all policies except UGB are globally welfare-increasing and capture most of the emission reductions. They also point to high heterogeneity across cities and highlight that there is no one-size-fits-all optimal policy to mitigate urban transport emissions.

Another set of papers focus on the potential of land value capture to fund urban infrastructure investment. Viguie and Hallegatte [2014] do so for public transport networks in Paris, France; and Avner et al. [2022] for flood mitigation works in Buenos Aires, Argentina. They both find that, in most cases, the land value creation would be sufficient to justify the investments.

Still another set of papers look at flood management policies through the lens of moral hazard. Avner and Hallegatte [2019] study three strategies - risk-based insurance, zoning, and subsidized insurance - within the context of Paris, France. Liotta et al. [2023] refine their approach. They both find that in a first-best setting, risk-based insurance maximizes social welfare. However, depending on flood characteristics, implementing a zoning policy or subsidized insurance is close to optimal and can be more feasible.

- Pfeiffer et al. [2019] provide a strong methodological contribution by making the model polycentric, and by introducing heterogeneous income groups, as well as informal housing situations that coexist with market and state-driven formal housing.

This last point is important to adapt previous approaches within the context of developing countries 3. As a proof of concept, Pfeiffer et al. [2019] simulate a UGB policy in Cape Town, South Africa. They find that demand for informal housing increases as a response to associated land supply restrictions and the higher formal land prices that ensue, uncovering a key housing market mechanism that is mostly absent in developed countries. They also simulate different scenarios for the construction of subsidized housing and find that, in the specific case of Cape Town, more construction speeds up the substitution of backyarding to traditional informal settlements. This is a noticeable trend as ongoing discussions in South Africa revolve around the facilitation of such dwelling arrangements to increase access to affordable housing and to stimulate densification.

The version of NEDUM-2D developed here builds upon this model, by introducing vulnerability to flood risks as in Avner et al. [2022], but for the City of Cape Town (CoCT). The specific mechanisms that we uncover are detailed in Notebook: use cases.

In a similar fashion, Liotta et al. [2022] use it to study the impact of a fuel tax on both spatial and income inequalities (also in the CoCT). They find that the poorest households, living in informal settlements or subsidized housing, have few or no ways to adapt to changes in fuel prices by changing housing type, adjusting their dwelling sizes or locations, or shifting transportation modes. Low-income households living in formal housing also remain impacted by the tax over the long term due to complex effects driven by the competition with richer households on the housing market. Complementary policies promoting a functioning labor market that allows people to change jobs easily, affordable public transportation, or subsidies helping low-income households to rent houses closer to employment centers are also shown to be key to enable the social acceptability of climate policies.

Overview of the model

Our model is calibrated for the CoCT with data from the 2011 National Census.

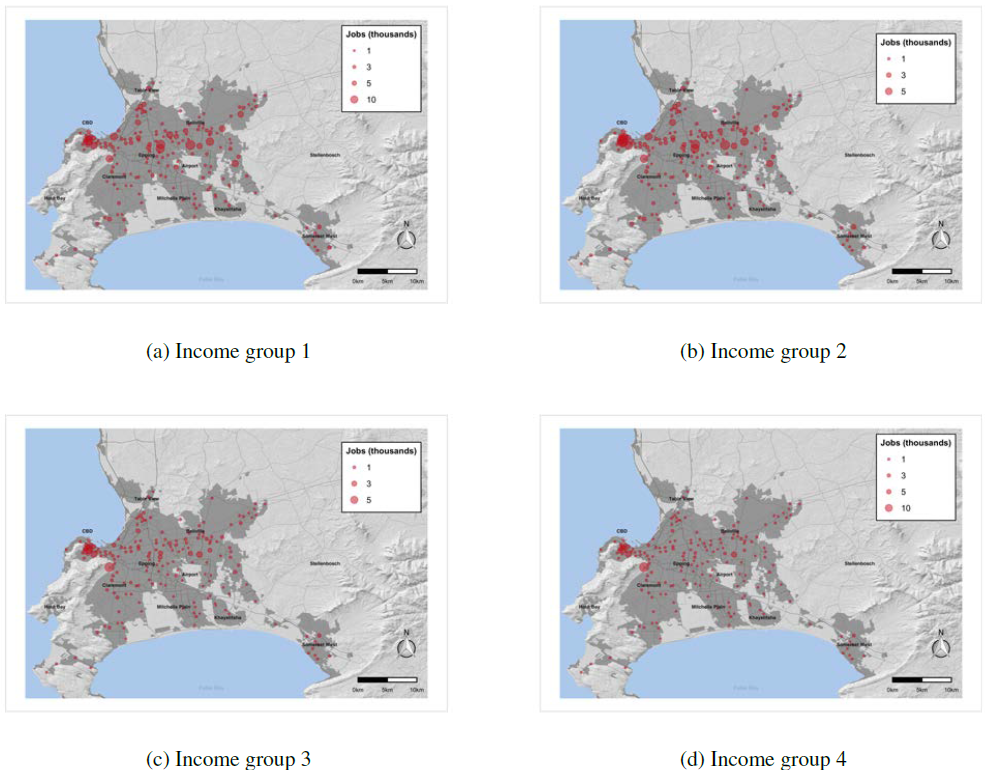

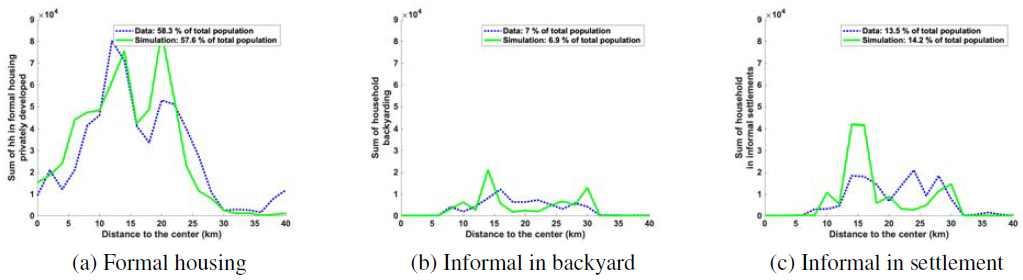

We consider four income groups (to study distributional effects) and four land / housing types: formal private housing (FP), formal subsidized housing (FS), informal settlements (IS), and informal backyard structures (IB). We assume that informal settlements are located in predetermined locations, and correspond to squatting described in Brueckner and Selod [2009]. We also assume a rental market for backyard structures erected by owners of state-driven subsidized housing as modeled by Brueckner et al. [2018]. We then integrate these elements within a closed-city model (with exogenous population growth) and simulate developers’ construction decisions, as well as the housing consumption and location choices of households at a distance from several employment centers (while accounting for state-driven subsidized housing programs, natural constraints, amenities, zoning, transport options, and the costs associated with each transport mode).

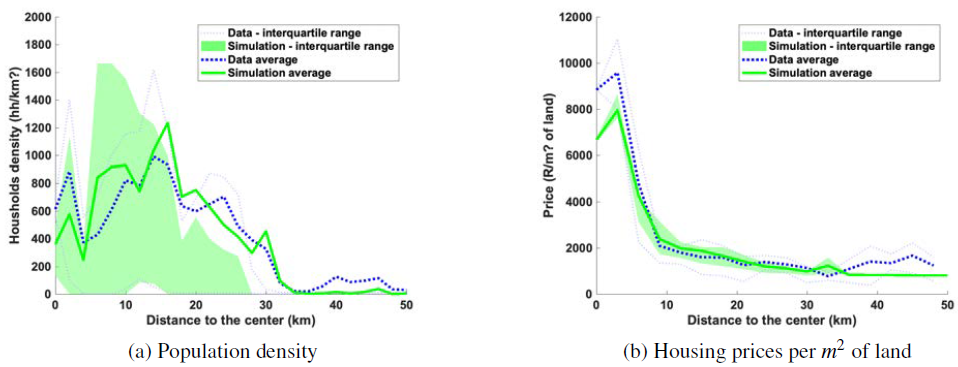

The model has displayed good performance, as shown by the validation plots below:

Comparison between simulation (green) and data (blue) for the year 2011 (Source: Pfeiffer et al. [2019])

Allocation of households to housing types and spatial distributions (Source: Pfeiffer et al. [2019])

Regarding flood risks, we distinguish between fluvial, pluvial, and coastal floods. Typically, fluvial floods are water overflows from rivers, whereas pluvial floods designate surface water floods or flash floods, caused by extreme rainfall independently of an overflowing water body. Coastal floods encompass storm surges, periodic tides, and gradual (if uncertain) sea-level rise. The associated risks that we consider are:

Structural damages: building depreciation caused by flood damages

Contents damages: destruction of part of households’ belongings due to floods

We believe that those are the main channels through which flood risks directly affect the city patterns [Pharoah, 2013] 4. Agents internalize those risks (or not) by considering the expected annual value of those damages (based on probabilistic flood maps) as an added term in the depreciation of their housing capital and of their quantity of goods consumed (assimilated to a composite good) 5.

As with previous versions, the model allows to simulate how households’ behaviour may evolve according to future demographic, climate, and policy scenarios. As a proof of concept, we develop two comparative statics in Notebook: use cases: one comparing scenarios with and without flood risk anticipation, and another one comparing scenarios with and without climate change.

Policies assessment

Mechanisms at play

Although distinct, the four housing submarkets represented in NEDUM-2D (formal subsidized housing, informal settlements, informal backyarding, and formal private housing) are linked through several channels.

First, with the exception of subsidized housing beneficiaries who receive a transfer from the State, poor households choose whether to live in formal or informal residential options so as to maximize their utilities.

Second, formal housing developers will decide how much floor space to build and where, based on formal private housing prices, which partially reflect the sorting of low-income households across formal and informal housing market segments. This in turn will influence poor households’ decision about what type of housing to consume and where until an equilibrium emerges.

Lastly, there is an externality associated with the use of land for informal settlements and publicly subsidized housing as these areas are “no longer available” for private formal housing development. This affects the supply and demand for formal private housing by restricting the set of potential locations available for formal private development, while accommodating a potentially large number of urban residents in the informal sector.

The specific mechanisms associated with flood risks are detailed in Notebook: use cases.

Interpretation of results

Prospective scenarios only represent conceivable futures that may inform cost-benefit analysis but have no predictive value per se, as many phenomena are neglected to preserve tractability.

NEDUM-2D relies on simplifying assumptions (exogenous land availability and subsidized housing, etc.) and stylized economic mechanisms (housing supply and demand) described above 7. Although it is calibrated to match observations in the baseline initial state, the number of parameters fed into the model is restricted to avoid overfitting and extreme sensitivity of the outputs to initial conditions.

Indeed, the aim of such a model is to provide simulations for the future, with the largest external validity possible in the absence of observable counterfactuals. For them to be informative, they need to display complex direct and indirect effects while keeping tractable the mechanisms that cause them, hence the need to restrict the number of such mechanisms that are interacting in equilibrium.

NEDUM-2D preserves the main market mechanism from the standard urban economic model, while allowing for sorting across different housing submarkets. If one is interested in the impact of other mechanisms on land-use patterns, one should probably consider another model.

Empirically, Liotta et al. [2022] - using a global sample of 192 cities - show that the standard urban economic model, despite its simplicity, has a strong predictive power in terms of population density, rent variations, and urban extent. However, they also show that the standard model performs less well in cities with high levels of residential informality, strong regulations and planning, as well as specific amenities. As we account for those elements in the Cape Town version of NEDUM-2D, there is additional motive to rely on the structure of this model. Still, as is commonly recognized in the literature, the biggest strength of the model is not to deliver predictions in absolute terms, but rather comparative statics that relate one scenario to another.

Footnotes

- 1

For a broader, less technical review of models used in spatial economics, see Glaeser [2008].

- 2

See Wray and Cheruiyot [2015] for a survey of land use modeling in South Africa.

- 3

See Duranton [2009] for a review of urban economic models within the context of developing countries.

- 4

Contrary to the so-called “Quantitative Spatial Economics” literature [Redding and Rossi-Hansberg, 2017], we do not endogenize employment locations, to the extent that we do not allow firms to compete with households for land. There are two main reasons for that. First, the (relative) numerical simplicity of the model allows us to deal with several dimensions of heterogeneity within an extremely granular setting. Second, survey data and expert opinion do not lead us to consider flood risks as a major potential shifter for job center distribution across the city. Since this is the focus of the current version, we therefore keep this distribution as fixed (more on that in Technical documentation) to focus on the direct mechanism described above. Then, our approach also comes with benefits of its own: we are able to model an endogenous city edge through the agricultural land (which is empirically relevant in a developing city context), and to simulate more realistic spatial sorting patterns through continuous (as opposed to unit) demand for housing, which is taken as a necessity good (more on that in Gaigne et al. [2022]). However, we would need a more general equilibrium model (with production, trade, etc.) to study the indirect impact of floods on overall economic activity (through infrastructure disruptions for instance, see Hallegatte et al. [2019]). We leave that for future work.

- 5

A possible extension of the current model would be to calibrate the extent of myopia in housing markets. Also note that such capital depreciation approach differs from the existing literature on sea-level rise [Desmet et al., 2021, Kocornik-Mina et al., 2020, Lin et al., 2021], which models flood damages through loss of available land. We believe that our approach is better suited to the study of (more general) extreme flood events that impact the value of land but do not lead to its permanent abandonment. This echoes our focus on within-city commuting rather than cross-city migrations (which we take as exogenous). Finally, note that all those studies abstract from modelling the economic cost of human life, which is likely to be non-negligible but is also hard to measure and subject to behavioral biases: in any case, incorporating such margin is only likely to reinforce our findings on spatial sorting.

- 6

The net effect on formal housing prices is ambiguous as the restricted supply of formal land should raise formal housing prices in the center, while pushing away population to peripheral areas where prices will be lower. At the same time, housing in the informal sector reduces the demand for formal housing, which exerts a downward pressure on formal housing prices.

- 7

See Technical documentation for more details.